Statement of Karl A. Racine, Attorney General for the District of Columbia

Before the Honorable Charles Allen, Chairperson, Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety

Good morning, and thank you, Chairman Allen and Councilmembers, for the opportunity to speak to you about the “Opioid Litigation Proceeds Act of 2022.” I am joined today by two of my colleagues from the Office of the Attorney General—Kate Konopka, Deputy Attorney General for the Public Advocacy Division, and Emma Simson, Senior Policy Counsel—who are available to help answer questions about the bill.

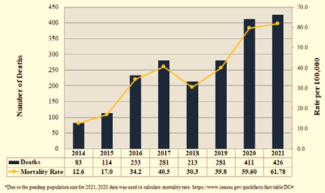

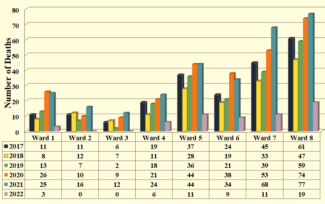

As you are well aware, in recent years, the opioid epidemic has inflicted immense damage on communities across the country. The District is no exception. Opioid addiction has disrupted the lives of many District residents and has had ripple effects on their families, friends, and communities.[1] Opioids have also claimed the lives of far too many District residents. Indeed, the District now has one of the highest opioid death rates in the country, and it loses hundreds of residents each year to opioid fatalities. In 2021 alone, the District reported 426 opioid deaths, nearly double the number of homicides that year. And in the five-year period spanning 2017 to 2021, opioids claimed the lives of 1,612 people in the District.[2] These deaths have been most heavily concentrated in Wards 5, 6, 7, and 8.[3] Nearly all involved fentanyl or a fentanyl analog.[4]

Figure 1: Number of Overdose Fatalities By Year, 2014-2021

Source: Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the District of Columbia, Opioid-Related Fatal Overdoses: January 1, 2017 to March 31, 2022 (June 17, 2022).

Figure 2: Number of Opioid Fatalities By Ward of Residence and Year

Source: Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the District of Columbia, Opioid-Related Fatal Overdoses: January 1, 2017 to March 31, 2022 (June 17, 2022).

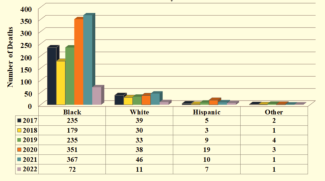

The opioid crisis has also exacerbated racial inequities in the District. Due to historical and ongoing discrimination, people of color face greater barriers to accessing care, including treatment and recovery services. That disparate access is almost certainly a factor in the staggering differences in overdose fatalities by race; in the District, 84% of those who died from opioid overdoses from 2017 to 2021 were Black, even though studies indicate that people of all races use illegal substances at similar rates.[5]

Figure 3: Number of Opioid Fatalities By Race and Year

Source: Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the District of Columbia, Opioid-Related Fatal Overdoses: January 1, 2017 to March 31, 2022 (June 17, 2022).

Sadly, this crisis did not occur simply by chance. Beginning in the 1990s, opioid manufacturers, distributors, and other entities downplayed the risks of opioid addiction and ignored signs of opioid misuse—all in pursuit of bigger profits. For the last several years, my office has sought to hold those actors accountable for fueling the crisis, by filing lawsuits to require them to provide resources to help our community repair the damage done. My office’s dedicated staff of lawyers, paralegals, and other professionals has spent thousands of hours investigating and negotiating with those companies to achieve a beneficial resolution for the District.

That work is paying off. Together with other state attorneys general, we recently finalized landmark settlement agreements with several of the companies involved in the opioid industry. Those agreements require the companies to make significant changes to their business practices. As one example, Johnson & Johnson can no longer manufacture or sell opioids or opioid products for distribution within the United States. And, particularly important to today’s conversation, the agreements require the companies to pay roughly $50 million to the District over the next 18 years to help address the effects of the opioid crisis, and another settlement could bring in an additional $30 million.[6]

Now, we must turn to the critical task of determining how to ensure that these settlement funds are used wisely to have maximum impact in abating the opioid crisis in the District. In taking on that task, we are not writing on a blank slate. The opioid settlement agreements we have reached contain requirements designed to ensure that the proceeds are used to repair the harms of the epidemic. For instance, our settlement with McKesson Corporation, Cardinal Health, Inc., and AmerisourceBergen Corporation includes a term requiring that at least 85% of the total funds that the District receives be spent on opioid abatement, and it sets forth a list of approved abatement strategies. Although that list is broad and allows for flexibility to fit local needs, the settlement specifies certain core, evidence-based strategies that must be prioritized.

Further, over the last several years, as our nation has grappled with the crisis, public health and other experts have identified a number of principles that ought to guide our approach to using the opioid settlement proceeds. First and foremost among those principles, we must ensure that the bulk of the settlement proceeds are used to support opioid abatement activities. Second, there is considerable evidence about what works in preventing and combatting opioid misuse and abuse.[7] For instance, there is extensive evidence that expanding community access to naloxone, expanding medication-assisted treatment, and providing cash and other rewards to individuals for adhering to treatment programs are highly effective methods for improving outcomes related to opioid use disorders.[8] Unfortunately, the District has, at times, been slow to adopt proven practices such as these.[9] In deciding how to spend the settlement funds we receive, it is critical that we rely on experts and available evidence to ensure that the money is spent on the most promising evidence-based and evidence-informed strategies and services. Third, we must ensure that our response is an equitable one that takes account of and seeks to redress existing disparities in residents’ access to prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm-reduction programs. Fourth, we must guarantee that those who have been most affected by the opioid crisis have a seat at the table. And finally, we must rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of our programs and services and guarantee public oversight and accountability for the use of these funds.[10]

The proposed bill before you—which is based on the Model Opioid Litigation Proceeds Act[11]—seeks to both ensure compliance with the settlement agreements and put these principles into practice. With respect to ensuring that the bulk of the settlement proceeds are devoted to opioid abatement activities, the bill requires that at least 85% of each settlement payment be deposited into a special Opioid Abatement Fund. That Fund can only be used to support authorized opioid abatement activities, such as providing grants to support evidence-based and evidence-informed prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm-reduction programs. The bill also specifies that all monies expended from the Fund must be supplemental to and shall not supplant funds that otherwise would have been expended on those activities. Further, none of the proceeds deposited into the Fund can, at any point, revert back to the General Fund, thereby ensuring that the settlement proceeds will be used to address the opioid crisis rather than other priorities.

As for implementing the other core principles, the bill directs the Mayor to establish an Office of Opioid Abatement, tasked with administering and overseeing a grantmaking process with certain guardrails about permissible expenditures to ensure the funds are used wisely. In particular, the grants can only be used for enumerated purposes, such as funding evidence-based and evidence-informed strategies and funding time-limited pilot programs and demonstration studies for strategies that are not evidence-based but show promise.[12] The bill also establishes an Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission to advise the Office of Opioid Abatement about appropriate goals for the Fund, key performance indicators, and grant awards and suspensions. The 11-member commission will ensure input from a range of stakeholders with valuable expertise and experience; it will include representatives from across District government, outside experts, and affected individuals, and it will hold public meetings to allow for even wider participation. The commission will review available medical and social-science research to identify the best evidence-based and evidence-informed strategies for combatting opioid use disorders, and it will apply that information to identify the approaches that best meet the District’s unique needs. The commission will also review data about disparities in access and outcomes to ensure that grants are awarded with an eye towards greater equity.

Further, to bolster public oversight and accountability, the bill requires the Office of Opioid Abatement to establish a public website containing a host of information, including information about the Commission’s work and grant awards. And to facilitate transparency and rigorous oversight, the bill requires the Mayor to submit detailed annual reports to the Council about the work being done.

To be sure, this bill represents just one step in a much larger effort to respond to the opioid crisis in the District. And OAG’s work to hold the opioid industry accountable is not done. We continue to pursue settlements with additional actors, and we hope that work will continue to bring critical resources to the District, to help reduce the number of families negatively harmed by this all-too-often-fatal epidemic. But, as the District begins to receive the first payments from the settlements finalized thus far, it is important that we create systems to ensure the funds are used equitably, effectively, and transparently. And it is important that we do so swiftly; until the Council passes legislation, the District cannot begin spending the settlement funds and cannot even receive certain of the settlement funds. I therefore urge the Council to move quickly to enact this bill so that our community can ramp up the work being done to redress the harms of the epidemic.

[1] As of 2017, an estimated 2,000 District residents suffered from an opioid use disorder. See Feijun Luo, Mengyao Li & Curtis Florence, State-Level Economic Costs of Opioid Use Disorder and Fatal Opioid Overdose—United States, 2017, Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report (Apr. 16, 2021), available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7015a1.htm#suggestedcitation.

[2] See Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the District of Columbia, Opioid-Related Fatal Overdoses: January 1, 2017 to March 31, 2022, at 1 (June 17, 2022) (OCME Report), available at: https://ocme.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocme/Opioid%20related%20Overdoses%20Deaths%206.17.21%20FINAL.pdf

[3] See OCME Report at 4.

[4] See OCME Report at 2.

[5] See OCME Report at 3; Colleen Grablick, Racial Disparities in D.C.’s Opioid Arrests Underscore Need for Decriminalization, Advocates Say, DCist (Aug. 29, 2022), available at: https://dcist.com/story/22/08/29/racial-disparities-dc-opioid-arrests/.

[6] Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy plan, which would require Purdue Pharma to pay the District roughly $30 million, is under review at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. If the plan is approved, the District could begin receiving funds in as little as four months after the approval.

[7] See, e.g., Evidence-Based Practices Resources Center, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, https://www.samhsa.gov/resource-search/ebp (last accessed Sept. 12, 2022).

[8] See Michael L. Barnett, et al., Evidence Based Strategies for Abatement of Harms from the Opioid Epidemic 8-10, 14, 32 (Nov. 2020), available at: https://www.lac.org/assets/files/TheOpioidEbatement-v3.pdf.

[9] See, e.g., Peter Jamison, Pure Incompetence, Wash. Post (Dec. 19, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/local/dc-opioid-epidemic-response-african-americans/.

[10] See Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Principles for the Use of Funds from the Opioid Litigation (last accessed Sept. 12, 2022), available at: https://opioidprinciples.jhsph.edu/the-principles/; Shelly Weizman, Sonia Canzeter, Somer Brown, & Taleed El-Sabawi, Maximizing the Impact of Opioid Litigation to Address the Overdose Epidemic (Mar. 2022), available at: https://oneill.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ONL_Opioid_Summit_5PG_Brief_P6.pdf.

[11] The Model Opioid Litigation Proceeds Act was developed by the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association, the Center for U.S. Policy, and Brown & Weinraub, PLLC, with financial support from the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, see Model Opioid Litigation Proceeds Act (Sept. 2021), available at: http://legislativeanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Model-Opioid-Litigation-Proceeds-Act-FINAL.pdf.

[12] As one example, the money could be used to support demonstration studies for supervised injection sites, a harm-reduction strategy that shows real promise. See Barnett at 34.